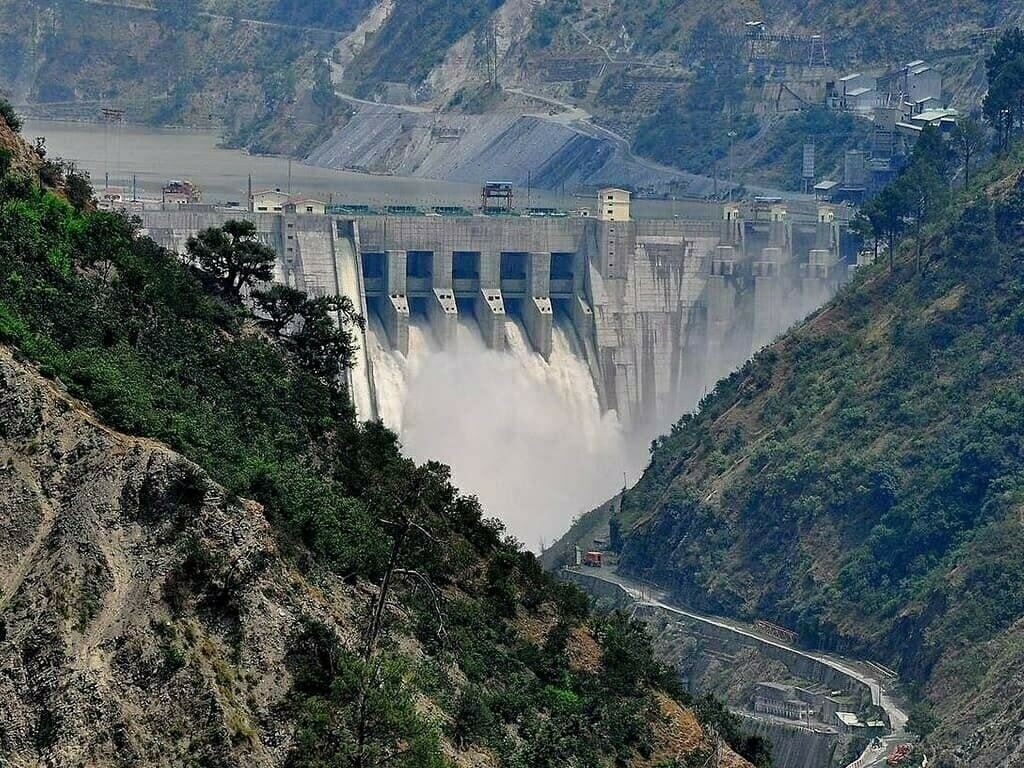

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam terror attack, the Government of India has effectively paused the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), taking a decisive step to reclaim control over its water infrastructure along the Chenab River in Jammu and Kashmir. A key part of this recalibration is the commencement of monthly sediment flushing at two major hydroelectric dams — Salal and Baglihar.

This marks a pivotal moment in India’s water diplomacy and energy strategy. Both reservoirs, managed by NHPC and the Jammu & Kashmir administration, were flushed earlier this month for the first time in decades, resulting in the removal of 7.5 million cubic metres (MCM) of sediment. This sediment buildup had long diminished power generation efficiency and structural health.

Subheadline: Long-Overdue Maintenance Now a Monthly Mandate

Until now, Pakistan’s objections under the IWT had restricted India from conducting such sediment flushing operations, arguing that it affected downstream water flows. With the treaty currently in abeyance, India is wasting no time asserting its right to uninterrupted dam maintenance.

The Central Water Commission (CWC) has now formally recommended that forced flushing be conducted every month at both Salal (690 MW) and Baglihar (900 MW) hydroelectric plants. A new standard operating procedure (SOP) for these operations is expected to be released imminently.

What is Sediment Flushing and Why Is It Critical?

Sediment flushing involves controlled water release from dam reservoirs to expel accumulated silt and debris that can severely impact the dam’s performance. Over the years, lack of flushing at Salal and Baglihar has led to:

- Reduced storage capacity

- Lower energy production

- Increased wear on turbines

- Higher risk of structural degradation

Now, with monthly flushing, India is expected to:

- Restore hydropower generation potential

- Extend dam longevity

- Improve downstream water quality and flow consistency

Subheadline: Strategic Shift in India-Pakistan Water Dynamics

The Indus Waters Treaty, signed in 1960, has long governed water sharing between India and Pakistan. Under its provisions, Pakistan controls the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers, while India has rights over the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej. However, India retains non-consumptive rights to build run-of-the-river projects on the western rivers — which includes dams like Salal and Baglihar.

Historically, Pakistan has contested many such Indian projects, claiming violations of flow and design parameters. The Baglihar Dam dispute, in particular, went to international arbitration in 2005, with the verdict allowing India to proceed with modifications.

Now, with the treaty no longer actively enforced, India is free to pursue dam operations like sediment flushing without seeking clearance from Pakistan — a significant geopolitical and environmental shift.

Energy, Environment, and Autonomy: India’s New Water Agenda

Monthly flushing is not just a maintenance protocol; it’s a symbol of India’s evolving water governance philosophy. By enforcing routine flushing, India aims to:

- Enhance energy security in Jammu and Kashmir

- Protect its hydro assets from long-term sediment damage

- Minimize future disputes over water usage rights

- Maximize its allowable share of Indus basin waters

Experts suggest this could pave the way for similar SOPs at other run-of-the-river projects in the Himalayan region.

Policy Outlook: What to Expect Next

As India prepares to institutionalize monthly flushing at Salal and Baglihar, the broader vision includes:

- Comprehensive dam maintenance schedules

- Enhanced inter-agency coordination (NHPC, CWC, J&K government)

- Possible replication at other Chenab and Jhelum projects

- Strategic review of water-sharing protocols with neighboring countries

The move also strengthens India’s stance in future dialogues with Pakistan or international observers regarding the status of the IWT, making it clear that security and sustainability will now shape water diplomacy.